Why Does Your Favorite Job Makes You Disgusted?

One day, I was assigned on an internship to gain exposure to a promising new project. My role was to handle incidents at the first line of support.

Seated nearby was a group of young people, fresh out of university. At first glance, you could tell they were a little beaten down, with that constant look of quiet despair in their eyes.

Trying to lift the atmosphere, I decided to strike up a conversation with one of my colleagues and started gently. When I asked what she wanted from this job, she answered with disarming honesty: “I’d like to stop spending every evening thinking about quitting.”

Problems of wizards

The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by exertion of the imagination.

I work as a wizard. Together with my colleagues, I embody thoughts into magic that changes the world. And I love my job. My wife is jealous, of course, but you can't command your heart.

I want to be a good wizard. I want to make programs that will benefit as many people as possible. I want my work to increase my level of competence and my social status. I want the results of my work to be recognized by the community and adequately appreciated.

All these goals can be achieved with my participation in large software projects in the interests of large customers.

However, such projects, in addition to my favorite work, new knowledge, experience, money and recognition of significance, usually bring anxiety, restlessness, insomnia, nervous breakdowns, severe headaches and burnout. As a result, a persistent aversion to the former object of adoration is formed latently and imperceptibly. For some reason, this doesn't make my wife happy either... As one of the greats once said: "It's not that love goes away that's scary... It's that it goes away unnoticed." After projects like these, you don't want to be a wizard anymore. Unless, of course, you've crossed over to the dark side.

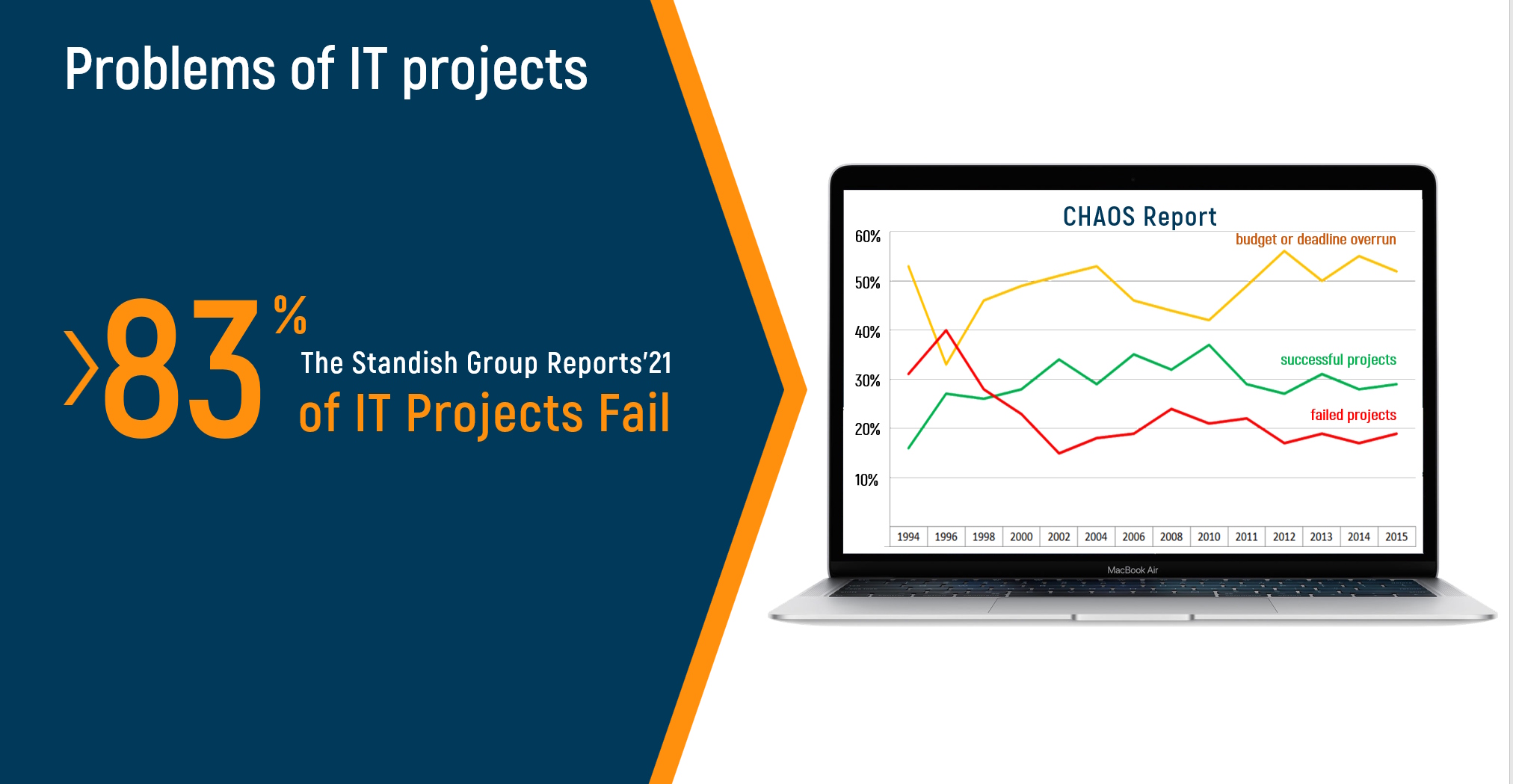

According to the Standish Group conclusions drawn from the analysis of the work results of more than 50,000 companies are disappointing: more than half of software projects partially or completely fail . The rather epic title of the annual reports that this organization regularly provides on the state of affairs in the world of software production is indicative - "CHAOS Report". According to the results of these reports, the main factors of unsuccessful projects are noted again and again:

-

incomplete and ambiguous requirements and their frequent changes during the project implementation to the point of losing relevance;

-

unrealistic expectations of customers in the absence of a desire to cooperate with developers;

-

poor quality of management, which includes a lack of planning for project teams and a lack of support from company management;

-

lack of resources and incompetence of performers.

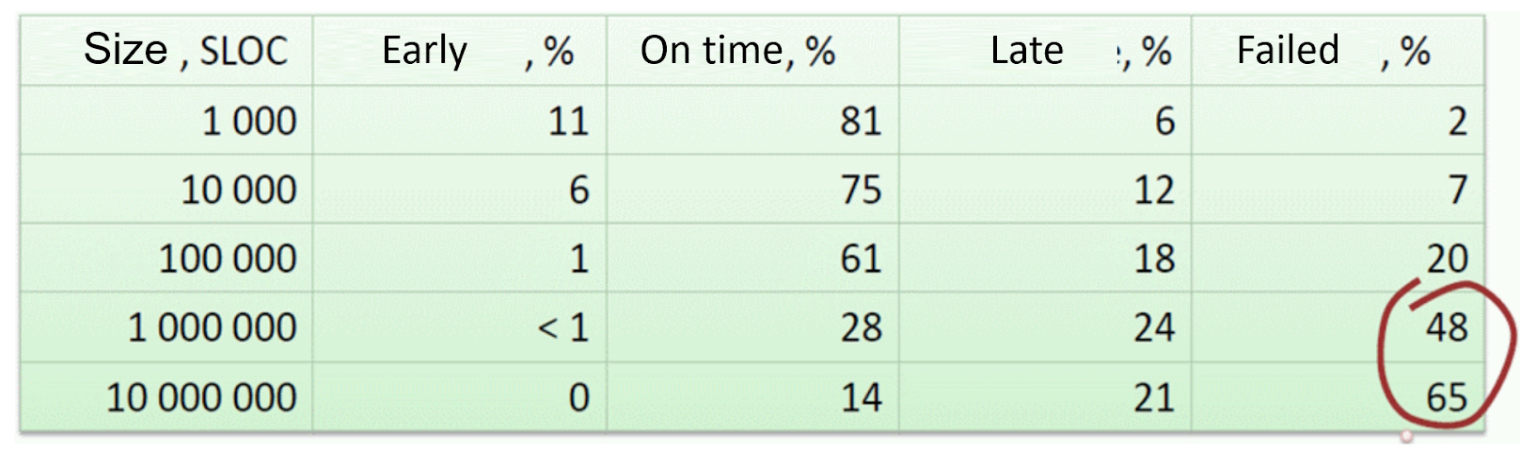

The world is unfair. The larger a software project is—the more good it could potentially bring—the higher the chances it will end up in the graveyard of failed projects. Experts note that the decline in the failure rate of software projects at the beginning of the century was not due to improved production efficiency, but rather to the shrinking share of large-scale projects in the software industry. Of course, sometimes the problem of large project success can be solved by breaking them down into smaller ones. Long live Agile! Instantly, the weight of the third major cause of failure drops dramatically. But what do you do in cases where you simply can't "cross a chasm in several small hops"?

No, this is not statistics, this is some kind of depressive black magic. Fortunately, all this statistics was not collected in Russia. But I am tormented by vague doubts that some correlation still exists...

Source: Sergey Arkhipenkov. Project evaluation: quackery or shamanism

Our project has long since passed the two-million lines of code mark. And every time a client sends another email asking us to "quickly" fix some "small thing," I can't say I'm thrilled at the prospect of having to perform yet another miracle… More often than not, it requires a very different kind of magic than the one I actually love.

My guess is that what really causes anxiety, insomnia, nervous breakdowns, and severe headaches are the daily fears. Daily fears in particular. Everyone knows that someday they will die, but generally that thought doesn't bother them.

What I need is an antidepressant that will save me from burning out on large software projects for major clients.

But in order to prescribe the right medication, the illness first needs to be diagnosed.

Phobias of honest employees

Let's immediately exclude from the study those reasons that are associated with an unstable psyche and have been duplicated many times on the Internet: fear of inadequacy for the position held, fear of delegation, fear of loss of respect, fear of being unclaimed.

What might a responsible, smart and honest employee be afraid of? For example, an executor who is a professional in his field or an experienced manager who is not afraid of political intrigue? I will try to guess the daily fears of each of the typical characters of a large software project.

What is the performer afraid of?

-

My work will be undervalued;

-

I will be assigned to do work that no one needs;

-

I will be assigned to do work that does not correspond to my skill level;

-

I will have to toil overtime;

-

I will have to toil, and the successes will be attributed to someone else;

-

All the mistakes of the privileged employees will be blamed on me;

-

All the mistakes of the managers will be blamed on me;

-

I will have to write unnecessary reports on the work done;

-

Everyone will find out that I do not know how to do the assigned work;

-

I will let my colleagues down;

-

I will do my work with insufficient quality, people will suffer.

What is a project manager afraid of?

-

I will show my incompetence;

-

I will forget an assignment from management;

-

I will forget some requirement from the customer;

-

there are so many tasks that I don't know where to start;

-

my employees will not complete the assigned tasks on time;

-

I don't have real tools to influence the team;

-

I don't know how to convince management that the deadlines are unrealistic;

-

I don't know how to convince management that additional specialists are needed;

-

I don't know how to prove to management that the decisions they have made are leading to disaster;

-

I am setting incorrect work priorities;

-

I will sign up for impossible conditions;

-

my work is undervalued;

-

the work of my team is undervalued.

What is a department manager afraid of?

-

I will show my ignorance of the state of affairs on projects;

-

I will underestimate the risks;

-

I will overestimate the available resources;

-

the project deadlines will be missed;

-

the customer will demand payment of a penalty;

-

I will miss an important point of the contract.

What is the company director afraid of?

-

The project will not pay off;

-

My partners will let me down;

-

I will ruin the company's reputation;

-

I will look unauthoritative.

What are the customer's representatives afraid of?

-

I will violate the regulations/instructions/orders;

-

I will be appointed responsible for an error in the document;

-

I will be guilty of accepting a low-quality product.

Prerequisites for depression

85% of the reasons for failure are deficiencies in the systems and process rather than the employee. The role of management is to change the process rather than badgering individuals to do better.

If all the employees on the project are honest, smart and want to do good, where would fears come from? There is no one to be afraid of. We are one team! Right?

However, fears are only symptoms that interfere with life. The truth is that these symptoms, unlike cough, runny nose and watery eyes, are not obvious. No one wants to publicize their fears. Recently, many drugs have appeared that can reduce the unpleasant sensations of the disease for a whole half day. True, they help in treatment as much as powder saves from pimples. Good doctors treat the cause.

If your employees constantly have acute respiratory diseases in the winter, maybe you should check the premises for drafts and heating? If your fears coincide with the above, I will try to guess from which corner you are blowing.

Lately, there are almost no job offers for project managers that do not contain the sacred words Scrum and PMI (PMP). But can these miracle frameworks really be applied to large software projects? "Of course!!! And how could it be otherwise!!!" - the vast majority of YouTube coaches will try to convince you. Against the background of this unbridled enthusiasm, the article " Managing the Development of Large Software Systems " by Dr. Winston Royce, Director of the Lockheed Software Technology Center, published in August 1970 in the US in the IEEE magazine, sounds much more convincing than Ivan Selikhovkin's "Scrum Black Book". And what Royce did not talk about is "quoted" again and again. It's a pity that Ivan did not write a book called "PMBOK Black Pages".

Inspired by smart books, I have also tried to apply these methods to live project teams more than once. However, my attempts, as a rule, brought more harm to the projects than good. At first, I thought that I was doing something wrong. After all, somewhere it really works.

And it really works. I checked. On product projects. On small projects, in which the interests of a commercial customer are represented by one person. In the case of small businesses - all the time...

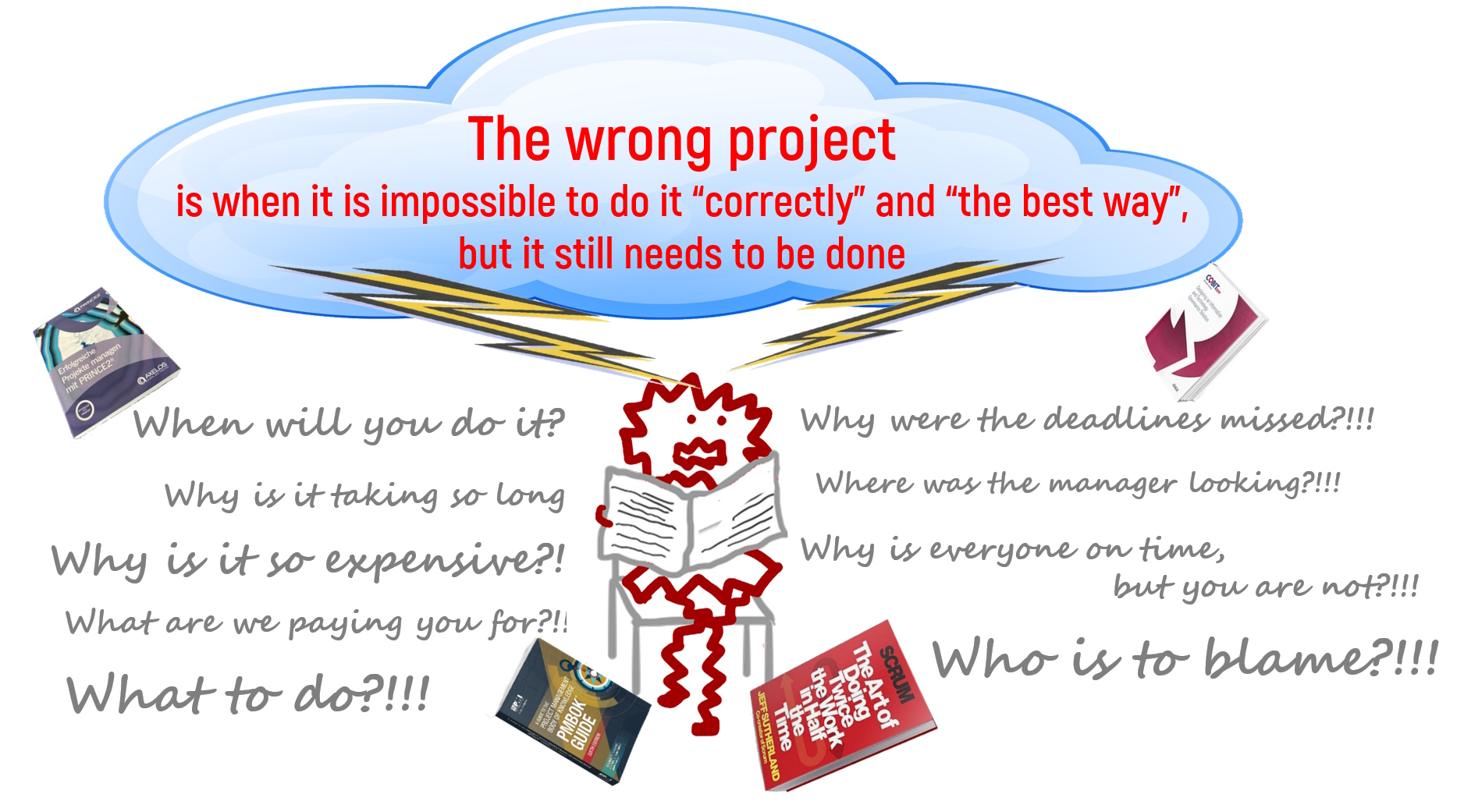

But on custom projects in the interests of large customers, it's not so good. Either the managers are wrong, or the projects.

Some managers, of course, are convinced that these methods work everywhere and under any circumstances. Whenever I come across yet another article about the "successful" adoption of Agile in some big corporation, I really want to believe it. Faith is a powerful thing. Even Napoleon once said: "If you believe in your victory, you've already won half the battle."

The trouble is, my own faith usually lasts only until I see the actual results of that Agile in practice. Apparently, their faith is stronger than mine… But then again, who would dare say the Emperor's new clothes aren't trendy? After all, if a 200-page Agile manual has been approved by every department head and signed off by the CEO himself, how could it possibly be wrong? As me was taught in the army: "If the chief of staff says a badger is a bird, don't argue—just start looking for the wings." And so, here we are: you will learn to love Agile—whether you like it or not.

And then - "clearly" according to the instructions:

-

There is no need to bother with the design documentation, we will formalize this waste paper later (one department head I know said so directly);

-

The main thing is not to spoil the relationship with the customer, we will not bother him with endless clarification of unclear requirements, we will make a product, and then we will agree;

-

There is no need to write plans, they are not implemented anyway;

-

There is no point in measuring the contribution of each employee - we are one team!

Some kind of total misunderstanding. For example, everyone understands that one of the most formidable predators on the planet - the killer whale, will not show its qualities at all in the middle of the Sahara. But not everyone understands where it is worth using imported effective management methods, and where - not.

On the other hand, what else is there to use? What's really out there on the generous marketplace? Something that doesn't make His Majesty the Manager think too much? Something you can just hand to your team in a book and say, "Here, follow this," and then leave them to it — they're smart, they'll figure it out.

A ready-made solution for every situation would be nice. So, what's on the shelf today? A dazzling assortment: Scrum, Kanban, XP, RUP, RAD, PMBOK, COBIT, PRINCE2, ITIL… Yes, I've tried all that already. Somehow, none of it really took root in our environment.

And what about those "corporate standards" the big companies like to flaunt? You know the ones — glossy binders full of processes that look suspiciously like they were photocopied straight out of a project-management textbook. A little rebranding, a few new acronyms, and voilà — a "unique corporate methodology."

But do they actually work? You say some organizations still use them? And their projects even manage to take off? Interesting. But let me clarify: I'm not asking about the launches. I'm asking about the safe landings. Have any of those been recorded — repeatedly, and at scale? Ah, you thought I meant something else… No, I was talking about something quite different.

As my not very representative research shows, more experienced managers, imitating Agile, cultivate an old, proven method called "Master and serfs". Isn't this the management method used on your project? Maybe this is where the reasons for your discomfort lie?

Of course not, why slander! Our king manager is kind, smart and fair. Not like others. He doesn't demand anything extra, doesn't make you catch jerboas, everything is to the point. Of course, you can't remember everything he said there…

This situation was very well described by Andrey Tyslenko:

"We conducted an experiment. Not a dozen times. Not a hundred times. We take and question the director. Give a list of tasks that you set over the last month. Of these, indicate those that you consider completed. Then we take all the people who sit under the director and ask them a very simple question: write down all the tasks that you received from the director and that you consider that you have completed. It turns out to be a funny thing. In the case, even when there is already information control, but there is no person assigned who consistently and step by step a) records and b) monitors the implementation, then the highest percentage of intersection of these tasks is 6% (six percent)".

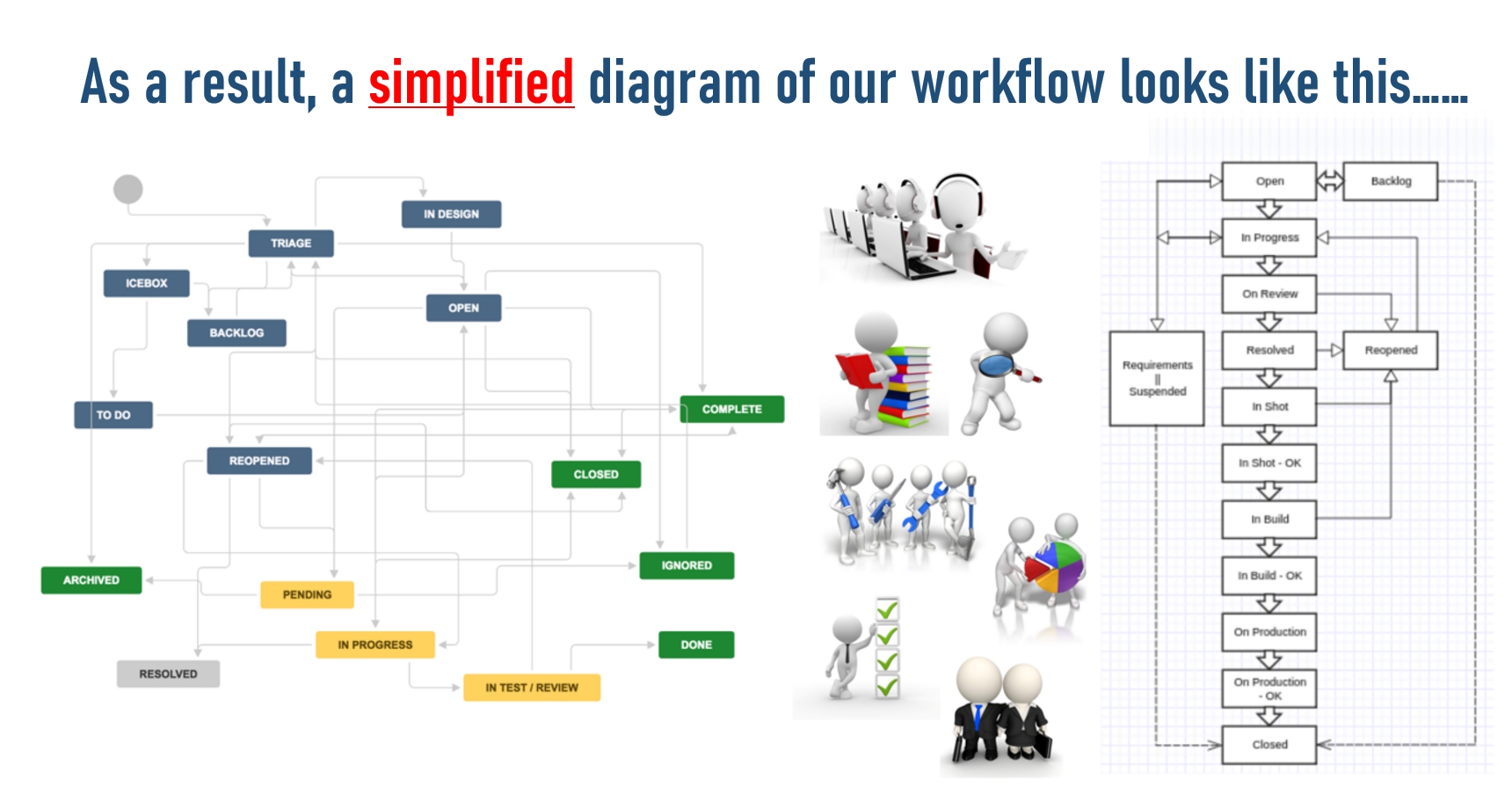

Only if we admit that what was said above is true, it already feels a bit uneasy. It immediately becomes clear that the orders of the boss need to be written down somewhere. So that it would be possible to understand what has been done and what has not. My statistics of communication with people like me show that JIRA is best suited for use as a common notebook on software projects. And all the main tasks are written down there. At the same time, all tasks are divided into types, and for each type, as a rule, a workflow is designed. We need to get rid of the mess! Create a perfect workflow . For each type of task. And assign a responsible person to each stage.

This is only for two types of tasks… Just one quick glance at these schemes makes my brain start whining pitifully about its genetic inferiority and handicap. Well, that's understandable. A project is a complex organizational system. It's clear that it won't be possible to cover all the details, because you can't formalize processes for all occasions. The main thing is to observe the Pareto principle . True, up to 80% of the activity may remain out of sight. But this is an unimportant 80%. At least, unimportant for now. And anyway, who knows how to predict this creative work.

The main thing is not to forget anything in the workflow, otherwise you'll get tired of synchronizing statuses. But if you build such workflows, you can always tell what state the execution of a particular important task is in. True, you can't always say who is to blame in such a situation. Go figure. There are seven nannies for one task. But the system, it seems, is observed.

After all, Eliyahu M. Goldratt said:

"We all understand the systems approach. We know that to do it, we have to start not with one aspect or one function, but with all of them. And then we don't know what to do with it, and we go back to doing each of those aspects separately. I think we shouldn't give up.

We have to rely on the intuition that led us to realize that we should take a systems approach. Why do we say that we should take a systems approach? Because we know intuitively that if we do something in one function, it affects other functions, and what may look good locally may have a negative effect somewhere else, which means that we know that there are cause-and-effect relationships that cross functions. We know that a cause in one department can have consequences in other departments.

If that's the case, why don't we establish the cause-and-effect relationships before we decide what to do? Is it so hard?"

We all understand the systems approach. We know that to do it, we don't start with one aspect or one function, but with all of them. And then we don't know what to do with that, and we go back to doing each of those things separately. I think we shouldn't give up.

We should rely on the intuition that led us to realize that we should take a systems approach. Why do we say we should take a systems approach? Because intuitively we know that if we do something in one function, it affects other functions, and what may look good locally may have a negative effect somewhere else, which tells us that we know that there are cause-and-effect relationships that cross functions. We know that a cause in one department can have consequences in other departments.

If this is the case, why don't we establish cause and effect relationships before we decide what to do. Is it so difficult?"

It may not be difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships between tasks. JIRA allows this. Then what to do with these relationships?

I suspect that there is a certain dependence between the described working conditions and the fears of honest employees on the project. But this dependence must be proven.

To be continued…..

Several years ago, having made life difficult for more than one project team by trying to implement progressive management methods, I decided to start "from scratch" at my new job. At the same time, when organizing work on my project, I decided to do not what was "recognized" and "correct", but what, in my opinion, really helps to reduce the nervousness of the participants in the software project. JIRA was chosen as a platform for improving management efficiency, but the accounting of primary data was not organized in a completely traditional way. And my own tools were developed to analyze this data. I published the first results of this experiment on Habr in my article " JIRA as a cure for insomnia and nervous breakdowns ". From the very beginning, I assumed that this approach would be criticized to smithereens. But, unfortunately, there was unexpectedly little constructive criticism.

However, at present, this approach itself, without the use of physical and administrative violence, has spread to six project groups in our department. One of my team leaders from another small company, after much hesitation, tried to apply this approach to his team and somehow stayed with it. In addition to the tools described in the first article, additional dashboards have appeared that allow you to assess current project risks and more accurately formulate management actions for project team members.

However, many continue to wonder: "How exactly does JIRA help stop burnout on a project?"

But before answering this question, I decided to test my hypothesis regarding the existence of the above fears and their dependence on the project conditions. Is it really so or is it just my imagination?

Although I am, of course, a wizard and have a rich imagination, I am not a telepath or a psychic. And I have never been a company director. Therefore, to test my hypothesis, I conducted an open survey in which more than 400 employees of IT companies took part.

I plan to publish an analysis of the results of this survey, as well as tested schemes for using my antidepressant in one of my next posts.